The Washingtonians on the RMS Titanic

Five boarded the ship for its maiden voyage; only two survived.

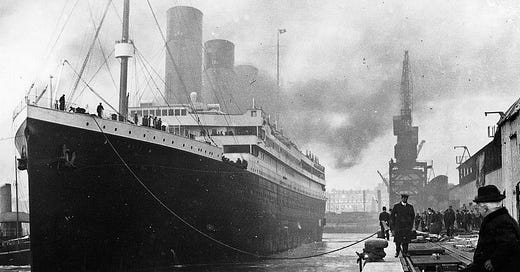

The maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic began on Wednesday, April 10, 1912, departing from Southampton, England, then stopping in Cherbourg, France that same day, where approximately 274 additional passengers boarded the ship. That evening, it sailed for Queenstown, Ireland, and on April 11 it headed into the Atlantic Ocean toward New York City with a total of 2,200 passengers on board. On the night of April 14, the ship struck an iceberg and sank two and a half hours later, with a loss of over 1,500 lives.

Five Washingtonians were first-class passengers aboard the Titanic for its fateful maiden voyage. They were Clarence Moore, Major Archibald Butt, Francis Davis Millet, Major Archibald Gracie, and Helen Churchill Candee. The following are their stories.

Clarence Moore, a noted sportsmen and horseman, had left Washington on March 16, 1912 to vacation in London and to purchase foxhounds for the Loundon Hunt in Leesburgh, Virginia, a live fox hunt that still continues today. On April 10, Moore, along with his manservant, boarded the Titanic at Southampton for the trip home.

Col. Archibald Gracie was a writer, soldier, amateur historian, and real estate investor. In early 1912, he had traveled to Europe on the RMS Oceanic alone, without his wife or their daughter. On the return trip, he boarded the Titanic at Southampton. Once aboard the ship, he seems to have assigned himself the role of keeping an eye on various unaccompanied older women, who included fellow Washington passenger Helen Churchill Candee, who had no need for Col. Gracie’s chaperoning.

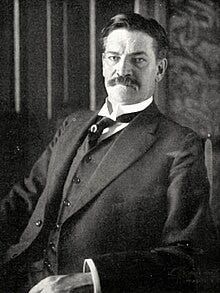

Major Archibald “Archie” Butt, then age 46, was an American Army officer, aide to Presidents Roosevelt and Taft, and close personal friend of Taft himself. Butt was concluding a six-week vacation in Europe along with a companion, 63-year-old Francis “Frank” Millet. Archie Butt boarded the Titanic at Southampton and Frank Millet boarded the ship at its stop in Cherbourg later that same day. They had shared a stateroom on their outbound voyage to Europe on the steamship Berlin, but took separate compartments on the Titanic. This may have been due the nature of their relationship, with Archie Butt feeling he was less likely to be recognized by the passengers on the Berlin; the high profile return trip on the Titanic would not provide the same level of anonymity for the pair.

Frank Millet was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1848. At the of 15, he was a drummer boy and served as an assistant to his father, a Civil War surgeon. Millet later graduated from Harvard with a Master of Arts degree. In addition to being an acclaimed artist and sculptor, he was also a writer, a decorated war correspondent, and served as vice chair of the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts. In 1879, he married Elizabeth ("Lily") Greely Merrill in Paris, with Mark Twain serving as his best man. He and Lily had four children together, but were seldom together themselves.

The relationship between Archie Butt and Frank Millet has been much discussed, with some historians ultimately concluding that it was a homosexual one. On the surface, it may have appeared simply as an arrangement of convenience between two single men in Washington—Archie being a confirmed bachelor, and Frank’s family living abroad. Archie only ever referred to Frank as “my artist friend who lives with me." But, the two men were inseparable and were considered very much a couple by those who knew them.

Archie and Frank ultimately moved in together in 1910 into a large house at 2000 G Street NW. There, they set themselves up with a cook and two young live-in Philippine houseboys. Together, they would entertain with large parties that were attended by members of Congress, Supreme Court justices, and President Taft himself. On one occasion, they threw an intimate dinner party to celebrate the completion of Frank’s portrait of Archie that was attended by President Taft, as well as their bachelor friends.

Helen Churchill Candee was an established literary figure, one of the country’s first professional interior decorators, and an activist for women’s rights. Although she had divorced her abusive husband and was raising two small children on her own, she managed to carve out a successful living as an author and journalist. One of her books, How Women May Earn a Living, became an international best seller, enabling her to afford a first class cabin on the world’s most expensive ship.

Helen Candee was traveling in Europe in the spring of 1912, completing research for her latest book, The Tapestry Book, when she received a telegram saying that her son had been injured in a car accident. From Paris, she hurriedly booked passage home on the Titanic, boarding at Cherbourg. On the voyage, she spent her time socializing with the other Washington passengers.

At 11:40 p.m. on April 14, four days into the crossing and about 375 miles south of Newfoundland, the Titanic struck an iceberg. Helen Candee was able to find a spot in one of the ship’s lifeboats, but had fallen and fractured her ankle in the process. She, along with another first-class passenger, Margaret “Unsinkable Molly” Brown, helped man the oars.

Unlike the other Washington men, Col. Gracie made it off the ship and survived by clinging to the rail of the topmost deck until the last. When the ship made its final plunge down to the sea floor, he was forced to let go and was caught in an eddy caused by the ship’s rapid sinking. After swirling around for what seemed an interminable time, he eventually came to the surface to find the sea a mass of tangled wreckage. Unhurt, he grabbed onto a wooden crate floating nearby until he managed to pull himself onto a large canvas and cork life-raft that had capsized. He immediately helped one man onto the raft, and then began rescuing those who had jumped into the sea and were floundering in the water. When dawn broke, there were thirty people on the raft, standing knee deep in the icy water and afraid to move lest it be overturned. Hours passed before they were picked up by the RMS Carpathia.

Accounts vary widely about the last minutes of the Washington men who remained aboard the ship. According to Col. Gracie’s testimony before a Senate Commerce subcommittee hearing soon after the tragedy, at around 2:00 a.m. Clarence Moore, along with Archie Butt, Frank Millet, and another first-class passenger, Arthur Ryerson, had returned to their usual table in the first-class smoking lounge to play a final hand of cards.

Frank Millet’s body was later recovered by the cable boat Mackay-Bennett and returned to East Bridgewater, Massachusetts. He was still dressed in formal evening clothes of a light overcoat, black pants, and a gray jacket. On the day of Millet's funeral, President Taft sent a large floral blanket for Millet's coffin. The bodies of Clarence Moore and Archie Butt were never recovered.

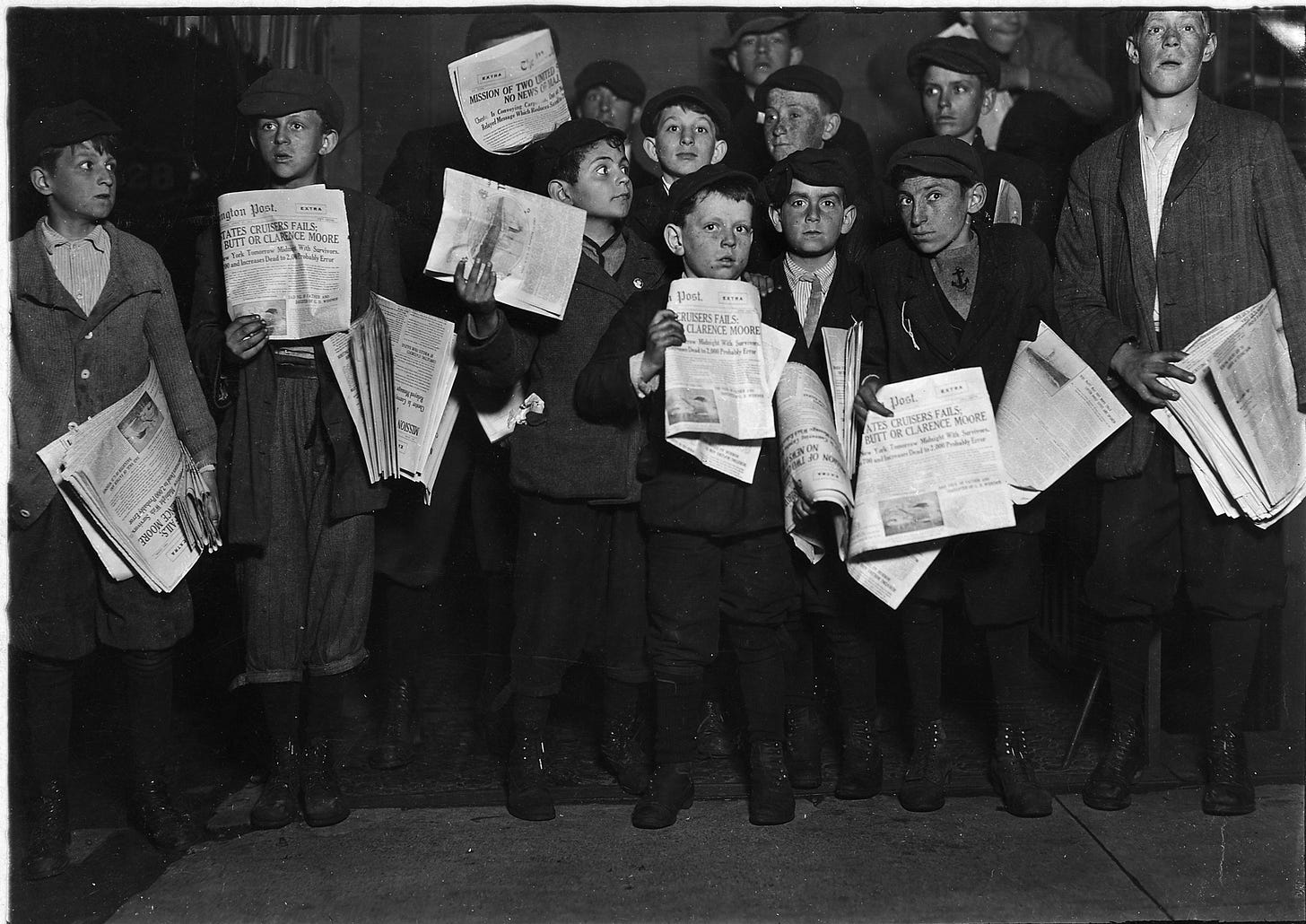

Washington anxiously waited for news about survivors of the Titanic. Not since the Spanish-American War had a national disaster held Washington at such a level of painful suspense. It was not until the RMS Carpathia reached New York that Washington knew the fate of its residents who had boarded the ship. When news reached Washington that Clarence Moore, Archie Butt, and Frank Millet were not on the ship, the city went into semi-mourning. Dinner parties at embassies and private homes were canceled.

Archie Butt’s first memorial service was held in the Butt family home with 1,500 mourners. President Taft spoke at the service. At a second memorial service, Taft broke down in tears shortly after starting his eulogy and had to end it abruptly. Taft also skipped the season-opening Washington Senators game in 1912 out of grief for Butt.

Col. Gracie became so obsessed with determining the cause of the Titanic’s sinking that his health failed. He fell into a coma on December 2, 1912 and died of complications from diabetes two days later—only eight months after surviving the sinking, becoming the first adult survivor to die. According to a New York Times article at the time of his death, his last words were reportedly, "We must get them into the boats. We must get them all into the boats." Gracie also died before he could finish correcting the proofs of his book, The Truth about the Titanic, which was published in 1913.

Although the ankle injury Helen Candee sustained while fleeing the sinking Titanic required her to walk with a cane for almost a year afterwards, by March 1913 she was able to join other feminist equestriennes in the "Votes for Women" parade down Pennsylvania Avenue, riding her horse at the head of the procession that culminated at the steps of Capitol Hill.

Two years after the Titanic tragedy, Helen Candee joined the Red Cross in Italy, during the start of World War I. A decade later, she was living in Beijing, where she became involved in the Chinese Civil War on the side of the Nationalists against the Communists, sending periodic dispatches from the front lines to the New York Times. She was nearly seventy years old at this time. After being decorated by the king of Siam for her 1924 book, Angkor the Magnificent, she retired to her summer home in York Harbor, Maine, where she died in 1949 at the age of ninety.

Memorials to the Titanic Victims

Of the two memorials to the Titanic victims in Washington, the first to be installed was a White House fountain in honor of Archie Butt and Frank Millet. The officially-given reason for the fountain was to honor the two Titanic dead who had been part of the federal government. While Butt was an Army officer and aide to both presidents Roosevelt and Taft, Millet had a mostly symbolic governmental role as vice chair of the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts.

In 1913, friends of Archie and Frank had raised enough money, and with the authorization of Congress, commissioned a memorial fountain for the two. President Taft approved sculptor Daniel Chester French’s design for the memorial and its location on the ellipse just beyond the White House South Lawn, where he could easily see it. It still stands there today.

For the second Titanic memorial, there was a design competition and the winning design by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was selected in 1914. The architect for the memorial was Henry Bacon, who previously designed the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial was finally installed in its original location along the Potomac River at the foot of New Hampshire Avenue in 1930, and dedicated in May 1931.

Some thirty years later, in order to make room for the Kennedy Center, the memorial was removed, placed in storage, and then later reinstalled at its current location at the Southwest Waterfront Park in 1968.