The Wadsworths Move to Washington. Their Gilded Age Mansion Now the Sulgrave Club

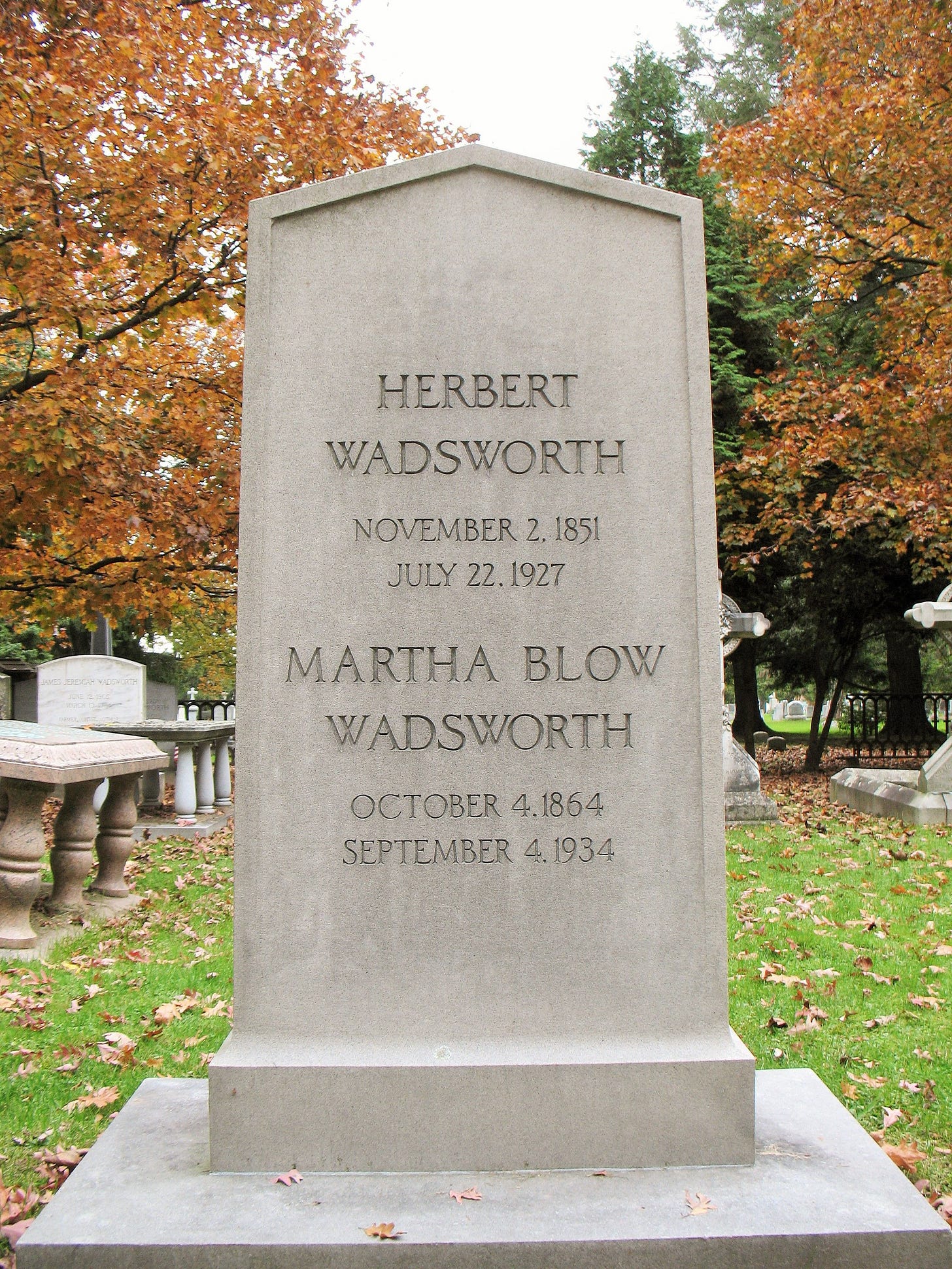

In the 1890s, millionaire gentleman farmer Herbert Wadsworth and his wife Martha Blow Wadsworth were enjoying country living on their estate “Ashantee” in Avon, New York. Herbert's life centered around the vast family landholdings and agriculture in the Geneseo Valley. Martha, who hailed from a distinguished St. Louis family, was an exceptional horsewoman, talented pianist, watercolorist, as well as a prolific photographer.

For the upper classes during the Gilded Age, winters were the time of the “social season” that took place between Thanksgiving and the beginning of Lent in several of the larger east coast cities. The season was marked by exclusive dinner parties, balls, house concerts, and other events. The Wadsworths would often travel from upstate New York for extended periods of time to participate in the seasons in Boston, New York City, and Washington.

When Herbert inherited a large amount of money from an uncle, now even richer and with no children of their own, the Wadsworths decided to move to Washington to build a grand winter home that would serve as a major social and entertaining center during the season in Washington.

Although many other wealthy Americans at this time arrived in Washington not knowing anyone and hoping to establish themselves socially, the Wadsworths already had family in the city. Herbert’s cousin, James Wadsworth, had been in Congress since 1881, and Martha’s late sister, Nelly, or Madame De Smirnoff, had been a well-known Washington socialite. Nelly’s daughter, Nelke, remained in town.

By the time they started looking for real estate in Dupont Circle, there were only two lots available directly on the circle itself— the most prestigious location in the neighborhood—that were large enough to accommodate the size of mansion they wanted to build. One was the site of Stewart’s Castle that was due to be demolished. The other was the abandoned Holy Cross Episcopal Church that had stood on a pie-shaped lot between Massachusetts Avenue and P Street NW for 25 years. In 1896, Charles Van Wyck’s widow, Kate, sold the lot, along with its deconsecrated church, to the Wadsworths.

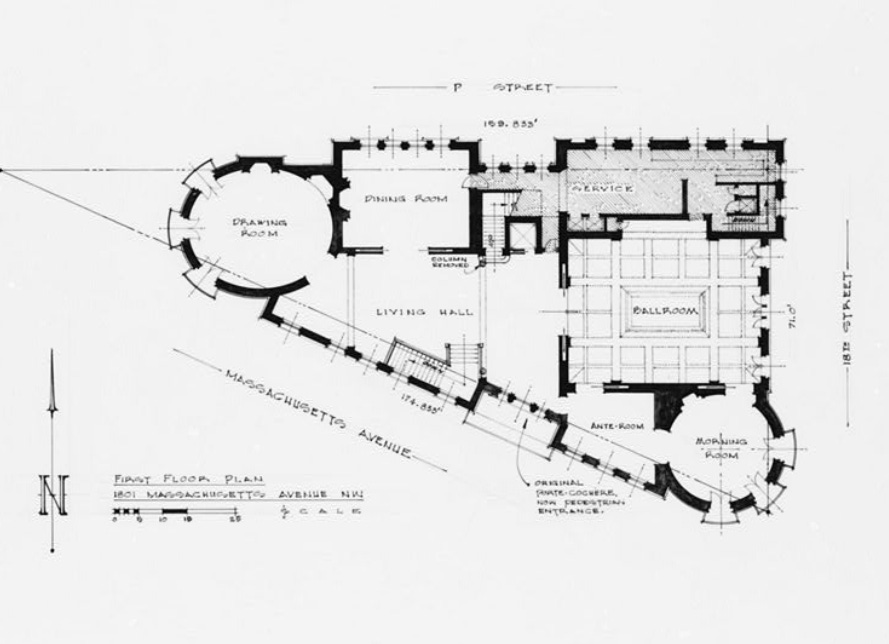

The Wadsworths chose local architect Frederick Brooke to design a house for the pie-shaped lot, although Martha often claimed she had designed the house herself. In addition to the Wadsworth’s house, Brooke's other notable works include the renovation of Dumbarton Oaks for the Blisses, the District of Columbia War Memorial, and the British Ambassador's residence, which he co-designed with Edwin Lutyens.

Construction of the 3-1/2 story yellow brick house at 1801 Massachusetts Avenue began in 1900 and by the time it was completed in 1902, the final cost exceeded $85,000 (over $3.2 million in 2025). The pie slice–shaped house was designed specifically for entertaining. Two floors were entirely devoted to drawing rooms, one opening into the next, ending at a dramatic two-story ballroom with a musicians gallery.

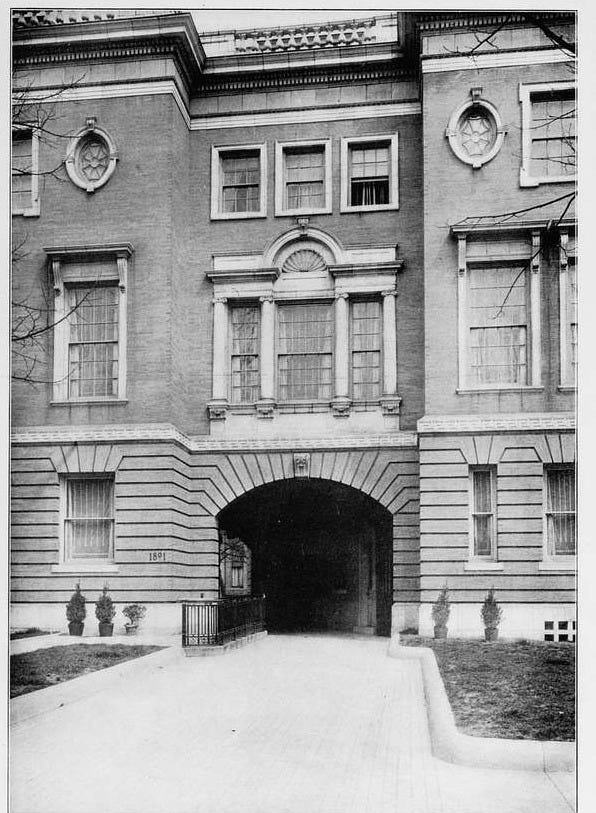

When the Wadsworth were designing the house, the electric car was all the rage and was quickly embraced by the Wadsworths. The house featured a drive-through carriage entry that went straight through the house from front to back, off which was the main entrance to the house. Opposite the main entrance in the drive-through was an “automobile room,” one of the first parking garages in the city equipped with battery recharging equipment and a car wash. Martha’s first Riker’s electric car, which sat in the automobile room, is now in the collection of the American History Museum.

Martha was always busy organizing some type of social event, either beauty lessons, a barn dance, or even jiu jitsu classes. She was one of the first women in America to achieve the rank of black belt in jiu jitsu. She also once organized an ugliest baby photograph contest, and her own husband ended up being the winner.

Martha was one of the early promoters of the musical arts for amateurs in Washington. She offered singing classes held throughout the season in her ballroom. The classes consisted of forty society women, and they would give small concerts at the house on Saturday evenings.

On Thursday evenings, Martha would host small dances with musicians playing waltzes and polkas. For these, she demanded a commitment from her invited guests at the beginning of the season: either every Thursday or specific Thursdays to be selected by guests in advance. Many were dismayed to learn that they were not expected every Thursday, but were thus considered second tier by Martha. Dinner was served at ten in the evening, followed by the dance. For these dances, the ballroom was often so dimly lit that guests could not see one another. When the Lent season arrived, the weekly dances were replaced with a musicale.

In 1902, the Wadsworths financially backed the creation of Washington’s first orchestra, the Washington Philharmonic Orchestra. Washington now having its own orchestra spurred an interest in music and served as an inspiration for Washington’s society people, including the Wadsworths, to offer musicales in their homes. These quickly turned into fierce competitions. Julia Bradley tried to outdo everyone by building a private, 500-seat theater in her home and bringing in the biggest Metropolitan opera stars from New York.

With all the competition to best each other, everyone agreed that Phoebe Hearst had the best musicales with performers including the Austrian-American contralto Madame Schuman-Heink, violinist Jan Kubelik, and violinist Fritz Kreisler’s own string quartet. These performers often charged between $2,000 and $5000 for their appearances at such events. Mrs. Hearst could certainly afford their asking prices, and it undoubtedly drove up the prices for everyone else. Martha Wadsworth took a more frugal approach to her own musicales, often selecting and promoting local amateur musicians.

With no children of her own, Martha took a matronly and protective interest in many of the young society women and their overall wellbeing. This was demonstrated one night when Martha woke up to find Marguerite Cassini, the Russian ambassador’s daughter, dumped on an upstairs sofa.

At the age of seventeen, Marguerite had decided to end her life over a failed romance. That evening, she had her coachman drive from pharmacy to pharmacy, collecting small portions of poison that she claimed she wanted to use to put down her ailing dog. When she thought she had enough, she took it all in the back of the coach. Her last stop was a drug store on Dupont Circle, where she suddenly changed her mind and called out for help. The driver immediately turned into the Wadsworth’s nearby carriageway.

Marguerite was carried upstairs and laid out unconscious on a sofa. Martha immediately called the doctor, who told her the only way to save her was keep her awake until the poison wore off. Martha was up to the task. She had Marguerite carried into the ballroom, laid on the bare floor and set to work slapping and punching her, rolling and dragging her across the room, and finally getting her to walk. Marguerite said she would preferred to die than continue to suffer through Martha’s treatment, begging to be allowed to, but Martha was determined that she would not. When morning came, Martha had won, and Marguerite lay on the floor still alive and sleeping soundly.

As the Wadsworths grew older, they spent less and less time in Washington. In the 1910s, they began to spend some of the winter months in South Florida rather than at their home in Washington—the winters in Miami preferable to those in upstate New York and Washington. In Florida, they also invested in additional real estate, purchasing two islands south of Miami between Biscayne Bay and the Atlantic Ocean: Caesar’s Rock and Meigs Key.

The Wadsworth’s Washington home was used in 1918 by the local chapter of the Red Cross and then only sporadically by the Wadsworths after the war when they were in town. It then stood empty for twelve years.

In 1932, five years after Herbert’s death, Martha sold the house to Dupont neighbor Mabel Boardman for $125,000 who converted it into the headquarters for the new Sulgrave Club for women. Boardman, who lived on P Street across from the Wadsworth house, brought together a group of friends and neighbors to both found the club and to prevent the property from falling into “undesirable” hands—had Mabel and the club’s Organizing Committee not acted when they did, the house would have become a Masonic Lodge.

While some of the eclectic interior of the house has been somewhat modified, much of its original detailing still remains. The carriage entrance is now the ground floor entrance hall.