The hanging of James McGurk in 1802—Washington's first judicial execution—was not simply an act of justice in the case of a poor man who killed his wife. It was a perfect storm of factors that ensured the death penalty for his crime: a newly-established DC Circuit Court, an oversight in the law, Thomas Jefferson's fear of appearing complicit in McGurk's other alleged crimes, and xenophobia.

Until 1850, only three judicial executions had taken place in DC. Although homicide was a common aspect of life in early Washington, the idea of hanging a man for a violent altercation with another, even if it resulted in a death, was alien to the minds of early Washingtonians. As a result, juries were more willing to convict a man of manslaughter, an act with no malice of aforethought, than wade into the murkier waters of motives or passion to determine degrees of murder.

Had McGurk not been an Irishman in Washington in 1802, and/or been tried only a year later, he might have been convicted of manslaughter and lived. But a conviction of first-degree murder and an execution provided the perfect opportunity to release increasing tensions between the locals and Irish immigrants in a small town.

James McGurk

James McGurk (sometimes spelled McGirk) was among the many Irish immigrants who were part of the earliest labor forces helping to build the new capital city. Many came as indentured servants as early as 1784 to work on the Potowmack Company, and later on the construction of the government’s public buildings. They also bought many of the house lots that the government had been unsuccessful in auctioning off to support its building campaign. They built homes on them, and quickly became an integral part of the population of the emerging city. Although they provided much of the city’s needed manual labor, these Irishmen lacked the necessary skills to enter into the artisan hierarchy and ended up working alongside slaves and freemen.

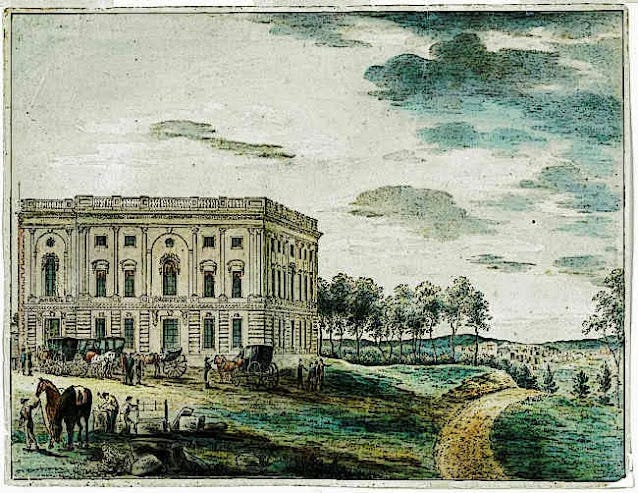

At the time, the criminal status of the Irish was suspect. Many of the indentured servants were, in fact, newly released convicts. Two cargo loads of Irish convicts were sent to work in Georgetown and Alexandria in 1785 and 1786. James Hoban, the construction superintendent of the White House and native of County Kilkenny himself, was accused of bringing with him a “company of thieves” when he arrived in Washington from Charleston 1792. Known locally as the “Mechanics,” the Irish would continue to be despised in Washington for the next sixty years.

McGurk had come to Washington from Philadelphia and found work as a bricklayer. Along with his wife, he settled amongst his compatriots on F Street between 12th and 13th Streets, NW. He was known for his drunken rages, often returning home drunk, quarreling with and beating his young wife. After a series of beatings in August 1801, she gave birth prematurely to twin boys. The babies had bruises on their bodies, and were either stillborn or died shortly after the delivery. Mrs. McGurk died several days later. Her death may have been the result of childbirth, the beatings, or a combination of both.

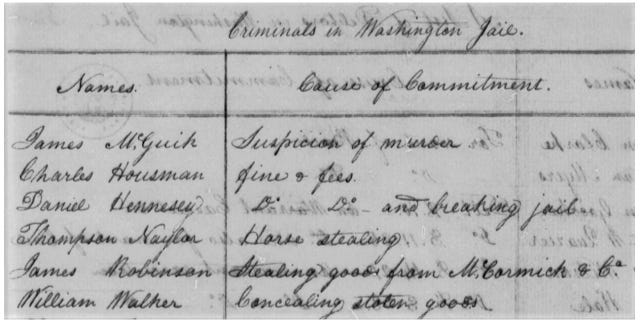

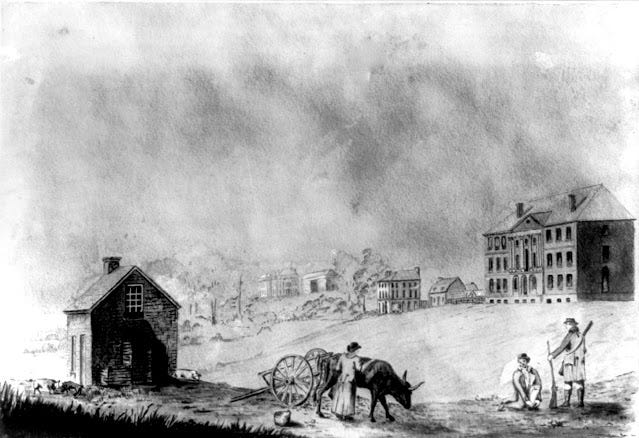

McGurk was arrested and jailed on charges of murdering his wife. The city’s jail at the time was nothing more than a small brick building consisting of three rooms that adjoined a bath house on the north side of C Street between 4th and 6th Streets, NW. In its day, it was the only bath house in the city, offering first-class accommodations. With no competition, its business flourished. By 1802, the lower floor served as a saloon and the rear was used for lock-ups where McGurk was thrown in with debtors, petty criminals, and runaway slaves. Over the years, this building would become known as “McGurk’s Jail.”

A Fledgling Circuit Court

The court that was to try McGurk had only recently been established and was at odds politically with the new Jefferson administration, When Jefferson, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party and rival to the Federalists, took office on March 4, 1801, he inherited two pieces of legislation that Adams had hoped would leave a permanent Federalist legacy on the country's legal system: the Judiciary Act of 1801, and the Organic Act of 1801. Also known as the "Midnight Judges Act," the Judiciary Act reorganized the federal circuit courts and increased the size of the judiciary, which was then filled by Adams's eleventh-hour appointments of Federalist judges, all with lifetime terms.

The Organic Act of 1801, also known as an “Act concerning the District of Columbia,” was an emergency measure taken when Congress realized that the land on which the nation’s capital sat had been overlooked and was without a uniform set laws or governance of its own. It combined five separate territories--Washington City, Georgetown, Washington County in Maryland, Alexandria, and the County of Alexandria into just two counties: the County of Washington, and the County of Alexandria.

The Organic Act also established a federal circuit court with a local jurisdiction to convene four times a year, twice in each of the two newly established counties. This court held the same status as the other circuit courts and consisted of three judges—a chief justice, and two assistant justices— who were also appointed for life. It also established the position of Attorney General of the United States to prosecute cases before the court. This new court covered not only federal crimes, but also any issue that would normally come before a court.

At first, Jefferson was powerless to do anything about Adams’s appointments of federal judges for the circuit courts. While he could not remove them directly, he simply changed the law that had created their positions. In 1802, the new Congress passed the Repeal Act of 1802 that abolished Adams's newly created circuit courts, putting the midnight judges out of their jobs.

Jefferson did not purge all of the Adams-appointed judges though. Being a practical man, he realized that Washington needed some form of a local legal system and governance and did not repeal the Organic Act. He also knew he would be able to exercise influence over its new Circuit Court with his own choices for its Chief Justice and Attorney General.

For the DC Circuit Court’s Chief Justice, Adams originally had hoped to appoint the highly esteemed Thomas Johnson of Maryland. Among Johnson’s many accolades were a revolutionary war hero, close friend of George Washington, the first governor of Maryland, District of Columbia commissioner, and former Supreme Court judge. But Johnson had been suffering from poor health for years, resigning his Supreme Court seat in 1793 and declined Washington's nomination for Secretary of State. Not unexpectedly, the 69 year-old Johnson declined the appointment to the Circuit Court as well, leaving the Chief Justice seat unfilled when Jefferson took office. Jefferson chose a Marylander and fellow Republican, William Kilty, for the seat in a hasty recess appointment.

For one of the court's two assistant justices, Adams appointed James Marshall, the younger brother of his appointment to the Supreme Court and Jefferson’s arch rival, John Marshall. For the second assistant justice, he appointed his wife Abigail’s favorite nephew and Federalist, William Cranch, who had been working as a land agent for the real estate firm of Morris, Greanleaf & Nicholson, which had gone bankrupt buying and trying to develop the city’s unwanted house lots.

Although connected to President Adams both politically and through marriage, Cranch quickly earned Jefferson’s respect. He had a reputation of being highly honest and moral, never wore the standard judge’s robe or wig, and yet was able to fully command his authority in the courtroom.

For Washington’s first District Attorney, Jefferson appointed prominent lawyer, John Thomson Mason. Originally from Virginia and a supporter of Jefferson in the elections of 1796 and 1800, Mason was so impressive a lawyer that Jefferson would later twice offer the position of Attorney General of the United States, which he declined both times.

The law governing all federal circuit courts was the Federal Crimes Act of 1790. It recognized two types of murder: first-degree (premeditated, or willful) and manslaughter (unpremeditated, or an act of passion), and established a separate set of penalties for each. For the penalty for first-degree murder, it specified death by hanging. For manslaughter, it specified imprisonment not to exceed three years, and a fine of no more than one thousand dollars.

The Prosecution and the Defense

McGurk certainly did not have the means to be able to afford a lawyer for himself. His court-appointed lawyer, Augustus Brevoort Woodward, was inexperienced and relatively unknown in Washington’s legal spheres.

Woodward was born in 1774 in Virginia. He may have received his college education from William and Mary College in Williamsburg, Virginia. Woodward had gotten to know Jefferson at Monticello when Woodward was teaching school while studying law in Rockbridge County, Virginia. Jefferson was not initially impressed by Woodward, but with their shared interests in the law and education, a friendship, if only a limited one, started to develop.

An ambitious individual and sensing opportunity, Woodward arrived in Washington and was sworn in to the bar in 1802. With Washington’s small bar of only eleven lawyers in 1802 and with a friend in the White House, the city provided a perfect venue for Woodward to launch his legal career. He was the first attorney to establish a private law practice in the new capital, yet his practice was so small that he could barely eke out a living. But opportunity did eventually come his way, not due to his reputation in the courtroom, but because he was the only private lawyer available at the time to defend McGurk. With Woodward’s friendship with Jefferson, McGurk’s hopes for a presidential pardon were undoubtedly heightened.

The Trial

The trial took place on April 10, 1802 and was over almost as soon as it began. Woodward was certainly no match for Mason in the courtroom, giving a poor showing against Mason’s well-prepared prosecution, possibly because he himself may have been convinced of his client’s guilt.

Mason was certain to make sure that McGurk would be convicted of first-degree murder and sent to the gallows. For his argument, he drew upon old English common law brought to the colonies in the 17th century, arguing that in order to reduce the charge to manslaughter, there had to be evidence of both passion and provocation, neither of which to him seemed to be present in this situation, nor was there any evidence of any motive produced. But, there were no witnesses to the murder or who could speak to McGurk's mental state or potential motives, so Mason’s assumption was ultimately not supportable. The only evidence admitted against McGurk were his dying wife’s declarations of his brutality, which with the lack of any witnesses, was allowable as evidence. This practice was carried over from the medieval English courts dating back as far as 1202, with the presumption that "no-one on the point of death should be presumed to be lying."

After the closing arguments, the jury deliberated only for a few minutes before finding McGurk guilty of first-degree murder. Although Mason had unsuccessfully convinced the jury that McGurk committed premeditated murder, or least that there was not any evidence that he had not, Judges Kilty and Marshall were divided on whether hanging was the most appropriate punishment—Kilty was in favor of death and Marshall was not, but for a jury’s conviction of first degree murder, the law required death.

The Sentencing

McGurk was brought before Judge Cranch to receive his sentence. Cranch was visibly pained in fulfilling this part of his duty for the first time. After he asked McGurk if he had anything to say, he proceeded to state that he had been found guilty by an impartial trial. He added that the offense was aggravated by the fact that the victim had been McGurk’s wife, who ought to have been protected by her husband than receive such barbarous treatment as to cause her death.

Cranch would later admit to Jefferson that no “adequate punishment, short of death” was available to the court. He could have meant that no other punishment was available as Washington had no prison at the time to incarcerate a prisoner for a manslaughter sentence. Washington’s first prison, where McGurk might have been sentenced if convicted of manslaughter was not to be completed until 1803, so Cranch probably did not want to risk embarrassment of handing down a sentence that could not be enforced.

When Cranch recited the words no one ever wants to hear, "... that you be there hanged by the neck until you be dead...," McGurk appeared unmoved and asked only for some time to prepare himself, which due to the delays that were to follow, he got more of than he could have imagined.

In reporting the verdict, the Washington Federalist newspaper took the opportunity to expound on the evils of foreigners in the city, namely the Irish:

"The prisoner was neither born nor educated in America. It is a matter of astonishment to those who are accustomed to attend our Courts of Justice to observe how few native Americans are found charged with the different crimes, which stain our records. How long can we expect our native youth to remain uncontaminated, from the examples were are constantly inviting to our shores?

Legal Confusion and Political Backlash

This first death sentence in Washington exposed yet another flaw in the city’s young legal system that led to extended anguish and suffering for McGurk and political embarrassment for Jefferson.

McGurk’s crime was committed and tried in the County of Washington, which was still governed by Maryland’s common law. Traditionally, the Governor of Maryland signed writs of execution against persons sentenced to death by any court in the state, but he no longer held jurisdiction over the County of Washington, and therefore could not sign a writ of execution for a man convicted in Washington.

A 1789 statute had given the federal courts power to issue writs of execution as needed “for the exercise of their respective jurisdictions.” But this language somehow had been overlooked in a 1792 rewrite of the statute and was not included. This omission was not realized until McGurk’s conviction.

Kilty and Cranch both assumed that authority in the District of Columbia lay with the President and did not consider it part of their duty to set a date and time for the execution. Still, not completely certain of their position, they asked the opinion of John Thomson Mason who agreed with them that that responsibility belonged with the President. But, while authorized to grant reprieves, pardons, and to commute sentences, the President did not have the Constitutional authority to punish, which included signing writs of execution. With the first death sentence, there was seemingly no one to sign the warrant for execution. Jefferson, one of the framers of the Constitution, immediately realized he had a predicament on his hands.

The day after the conviction, Jefferson wrote to both U.S. Attorney General Levi Lincoln and John Thomson Mason concerning the question of who was to sign the writ for McGurk’s execution. The following day, he received hastily written responses from both men, one contradicting the other. Lincoln wrote that he thought that for convictions in federal courts, the Constitution gave the authority to the President. Mason, who had originally agreed with Kilty and Cranch, had rethought his position, and had now determined that Congress had given the DC Circuit Court all the powers it granted to all other circuit courts whose duty it was to hand down sentences and issue writs of execution. Therefore, the signature of the President was not necessary.

McGurk began writing personal letters to Jefferson pleading for him to spare his life. The letters were written in another, barely literate hand, and signed by McGurk. But whoever actually authored the letters was clearly aware of the legal quagmire uncovered by the conviction. In the first letter, McGurk's ghost writer acknowledged the confusion as to who held the authority to sign the writ of execution, and whether the President thought the responsibility might ultimately fall upon himself, he might therefore consider granting a pardon. But Woodward initially thought his client’s letters were too intrusive to be delivered to the President. It may be the fact that Woodward had written them himself and was concerned that Jefferson might have detected this.

Jefferson ultimately took Mason’s advice and decided that the Circuit Court should set the date and time of McGurk’s execution in its upcoming July session. But due to the amount of time it took Jefferson to decide not to take action on the sentencing, McGurk would end up sitting in jail for three months before he would learn of the final date and time of his end.

When the Circuit Court finally convened that July, it set the date for McGurk's execution a month later on 28 August, now leaving McGurk sitting in jail for more than four months after his conviction. The accepted practice at the time was that an execution should be done within a reasonable amount of time--Virginia law granted a convict only up to thirty days to live after a sentence was passed.

By mid-August, time was running out for McGurk. Woodward realized that Jefferson was not inclined to intervene on his behalf to commute the sentence. Woodward may have been the first lawyer to have lost a capital case in Washington, but he would make up for it as an advocate on behalf of his convicted client.

He decided to make the long trip from Washington to Monticello to plead for McGurk’s life. Along with McGurk’s previously undelivered letters to Jefferson that Woodward held withheld earlier, he brought a petition with more than 150 signatures. The petition’s signers were some of the city’s leading Irish citizens including the architect of the White House ,James Hoban, Hoban’s real estate partner Pierce Purcell, architect John Kearney, and a number of other signers who had Irish surnames as well. The list of the petitions signers revealed how close-knit the Irish community was at the time and that it was undoubtedly concerned that one of its own was to be the first Washington resident to be sent to the gallows. This would not help their status in the city.

The petition argued that the extended amount of time that McGurk had already spent in “severe and rigid confinement,” due to Jefferson’s and the judiciary’s indecision should have been punishment enough for a crime that was not premeditated and intentional, and that the punishment was disproportionate to the offense, were it the result solely of his unfortunate temper and habits.

By now, Jefferson began weighing the possibility of a pardon for McGurk. But because Kilty and Marshall had been divided as to recommending him to mercy, Jefferson had also solicited Cranch’s opinion. While awaiting word from Cranch, and one week before McGurk was scheduled to be hanged, on August 21, Jefferson signed another week's reprieve for McGurk until August 28.

When the news of the reprieve reached Washington, it first came as a rumor that Jefferson had actually granted McGurk a pardon. After the news was corrected, the Washington Federalist newspaper—not a friend of the Irish or immigrants in general—rallied against the stay of execution: “the prisoner was neither born nor educated in America,” and that native-born Americans rarely committed such violent crimes. It also condemned immigration laws (namely those pertaining to the Irish) “that for the sake of gaining a few bawling patriots, would thus hasten the strides of vice, disturb the peace, and security of our country.”

Open wounds from the recent presidential election still festered and came to the surface. Some Federalists used the delays to argue that Jefferson was too lenient on McGurk, suggesting that he may have been an agent of Jefferson acting as one of a gang who lurked about Washington intimidating Aaron Burr’s supporters early in 1801, before the resolution of the presidential election in favor of Jefferson by the House of Representatives. Such rumors may have had an effect on Jefferson’s interest in pardoning McGurk. Were he to grant a pardon, he may have appeared complicit in McGurk's alleged actions. Others felt that McGurk was being scapegoated by Federalists as an agent of Jefferson and therefore unfairly tried by a court where two of its three judges were Federalists condemning him to an unjust sentence.

In September of 1802, William Cranch finally responded to the numerous letters he had received from Woodward and McGurk. They had hoped that Cranch had changed his mind and now sided with Jefferson in being opposed to McGurk's death sentence and in favor of a pardon, but Cranch remained steadfast to his original verdict. He wrote, “whatever I might be disposed to do as a private citizen, I can not, as a judge, recommend the criminal to the mercy of the President. The interests of society, which it is my duty to protect, demand that crimes like these should be severely punished.”

Three weeks after Woodward received Cranch’s letter, a copy of that letter reached Jefferson at Montecello. Cranch's response was the final and strongest opinion that Jefferson would hear from the three judges. Knowing that McGurk was now apprised of Cranch’s opinion, Jefferson became concerned that McGurk would try to escape and wrote to Washington’s mayor, Robert Brent, who was a fellow Catholic and parishioner with McGurk of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, recommending that he spare no vigilance to prevent his escape. The mayor responded quickly to Jefferson’s concerns and confined McGurk in a seven feet square room and shackled with nearly 60 pounds of irons. McGurk found no peace, with his ears assailed every hour of the day with the cursing and obscene expressions of the other prisoners. His small cell got very little air, and was covered with excrement from an adjoining apartment.

Five days before McGurk's scheduled hanging, Woodward made one final and desperate attempt to try to sway Jefferson. Jefferson received an anonymous letter, signed only as “Friend.” Although the letter was not in Woodward’s handwriting, Jefferson must have known that it was from him. Some of the phrasing used by its author was very similar to wording in documents and letters that Woodward had sent to Jefferson earlier and in letters he wrote to the Washington Federalist arguing against capital punishment for McGurk, going so far as to blame his wife for not having a strong enough constitution to endure his physical abuse.

Jefferson remained unmoved. McGurk sent two more direct appeals to Jefferson begging for clemency, the last arriving on the day of the execution. Jefferson did not respond to either of the pleas, and McGurk was to be hanged on October 28th.

McGurk's Execution and Burial

This was the first hanging in Washington, so a scaffold had to be constructed for the event. It was erected on the western grounds of Capitol Park in a grove of oak trees which stood a little north of the Pennsylvania Avenue approach to the Capitol Building. The scaffold could be seen from Pennsylvania Avenue, which was then little more than a country road. There were other few buildings along the way except the new jail, still under construction, and Blodget’s Hotel.

In the morning of an overcast October day in 1802, McGurk, attended by Father Young of St. Patrick's Parish who had been attending to McGurk’s soul, was taken from the jail in a cart to the gallows, surrounded by a strong guard, and followed by a mob of screaming, hooting men, women, and children all the way to the gallows.

After McGurk had climbed the thirteen steps to the top of the makeshift platform, he was asked if he had anything to say—the final courtesy given a condemned man. McGurk took a long look at the sea of eager, angry faces and exclaimed: “When a man’s character is gone, his life is gone.”

After the noose was placed around McGurk’s neck and before the sack was placed over his head, and as if looking to heaven, he cast his eyes upward to where the rope was fastened to the crossbeam. Suddenly, he jumped off the platform before the henchman could pull the canvas cap over his head. Father Young shouted out to him “McGurk, don’t hang yourself!" The hangman immediately ran up the steps and tried to pull McGurk back onto the platform. Swinging wildly at the end of the rope, the hangman only succeeded in getting McGurk’s feet back on the platform. McGurk then pushed off again. While dangling the air, someone hastily cut the rope that held the trap door on the platform to keep him from regaining his footing. After three or four convulsive shrugs, was dead. Following an old Medieval custom, immediately after the body was cut down, crowds rushed the scene and started cutting the rope hoping to secure a small piece thought to have curative powers.

Even though this was the first execution in the nation’s capital, it received scant notice in a local paper. The National Intelligencer simply stated: “Yesterday was executed James McGurk, sentenced to death for the murder of his wife.”

McGurk’s body was buried Holmead’s Cemetery, then a privately-owned family cemetery at the edge of the city (present day Florida Avenue and 19th Streets NW). He was placed next to a young woman who had been buried there the week before. Her brothers found out and when they informed their mother, she told them she would not regard them as men if they allowed the murderer to rest there. A group headed by a Mr. Sniverly, armed with shovels and torches, moved McGurk to another part of the cemetery. On a Sunday night, a large band of McGurk’s fellow Irishmen moved it back to the plot where it was intended and kept guard over it at night. Supplied with enough whiskey to pass the night, they awoke the next morning and discovered that the body had once again been removed by Sniverly’s band of men. This time, they buried the body close to the banks of Slash Run and damned the stream to change its course so that its water would run perpetually over the site.

Some 40 years later, the owner of some land south of the cemetery was digging a post hole and struck a human skull and some fragments of wood. One of Sniverly’s resurrecting party members admitted that it was the location where they had laid McGurk for his final rest.

Postscript

William Kilty resigned as Chief Justice of the DC Circuit Court in 1806 to become Chancellor of Maryland. He held that office until his death in Annapolis in 1821.

William Cranch was appointed by Thomas Jefferson in 1806 to become the Circuit Court's Chief Justice, filling the seat vacated by William Kilty. Cranch would go on to serve on the court for the next fifty-four years until his death in 1855 in Washington, D.C. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington.

Soon after McGurk's trial, Woodward left Washington for the Michigan territory, where Jefferson had appointed him as judge of the Territorial Court, where he served from 1805 to 1824. He would remain in Michigan for twenty years and would also be instrumental in the founding of the University of Michigan. In 1824, President James Monroe appointed him to a judgeship in the new Territory of Florida. Woodward served in that capacity until his death in Tallahassee in 1827 at the age of 52.

John Thompson Mason twice declined the office of United States Attorney General when it was offered by Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. He later ran for one of Maryland's seats in the United States Senate, but lost. Mason died on 10 December 1824 at the age of 59 and was interred at his Montpelier estate in Clear Spring, Maryland.

Holmead's cemetery became the burial site of many notable Washingtonians, including McGurk's compatriot and supporter James Hoban, itinerant preacher in the Second Great Awakening Lorenzo Dow, and William and Rhoda O'Neale, the owners of Franklin House. In addition to McGurk, another of the more notorious later burials there was also Lewis Payne, one of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, who was also to face the noose.

The city took ownership of Holmead's cemetery in 1820 and expanded it to become the Western Burial Grounds. The cemetery started going into steep decline around 1850, and in1870 it was condemned as a health menace. Cemetery record books accounted for over nine thousand burials within its small area, not including a large number of unofficial burials as well, of which McGurk may have been one. Removal of remains, most of which were reinterred at Graceland Cemetery or Rock Creek Cemetery, continued until 1885. James McGurk's remains were not among them.

* * * * * * * * * *

Copyright (c) 2024 Stephen A. Hansen. All rights reserved.