The year 1881 was a busy one for Philadelphia architect John Fraser. In addition to James Blaine’s house, he was also building a large house for Senator Charles Van Wyck of Nebraska on the other side of Dupont Circle at 1800 Massachusetts Avenue in Washington.

Charles Van Wyck was born in Poughkeepsie, New York. He completed preparatory studies and graduated from Rutgers College in 1843. He then studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1847, eventually moving to Bloomingburg, New York, where he became the district attorney of Sullivan County, New York in 1850.

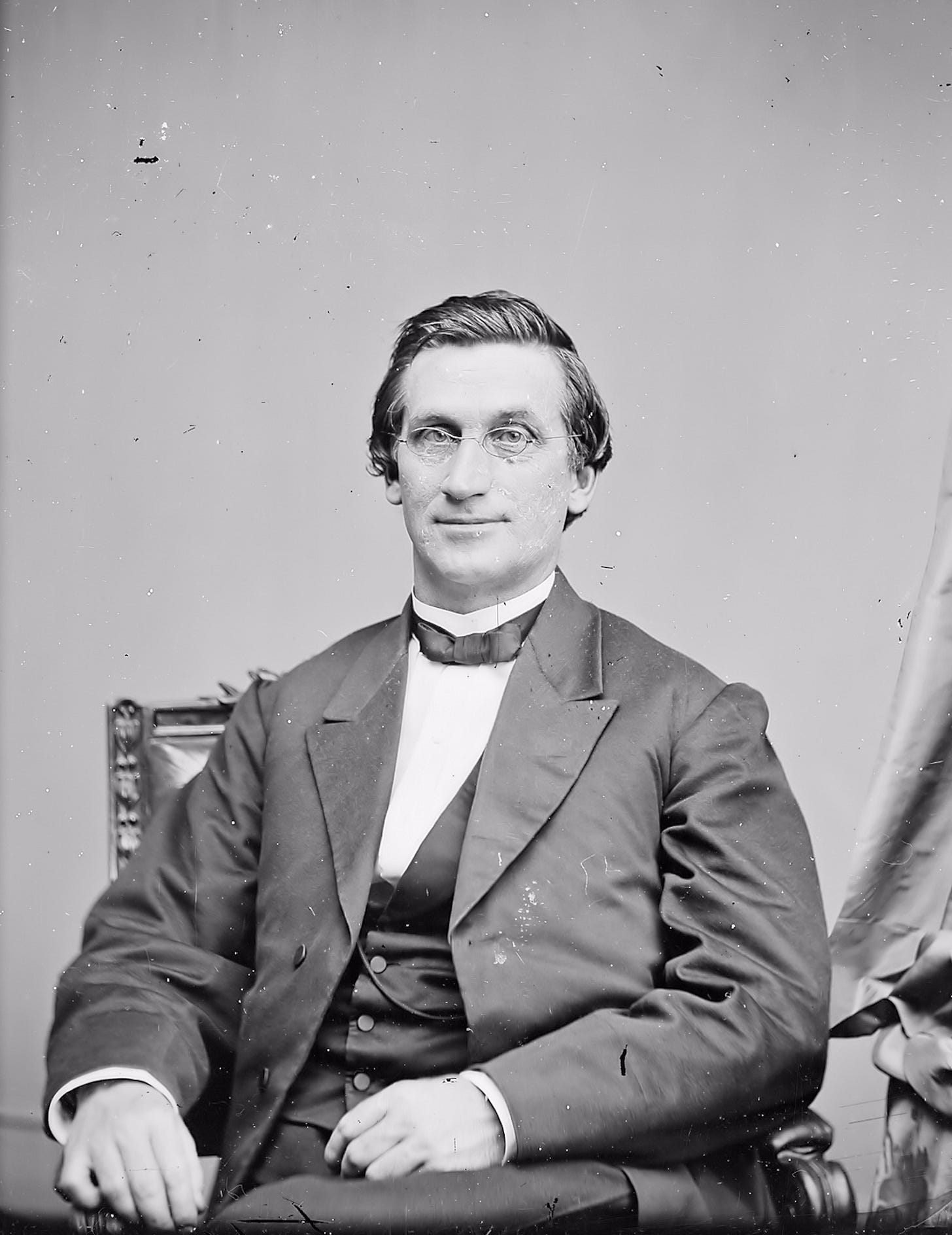

Van Wyck had inherited a sizable amount of money and was quite eccentric. Never concerned about his personal appearance, Van Wyck would never have been mistaken for a wealthy man. His appearance was often disheveled, with baggy clothes, collars gone awry, and black string neckties caught up around his ears. His enemies called him “Crazy Horse” on account of his jerky speech and gestures.

Van Wyck first came to Washington when he was elected to Congress as a Republican from New York, serving two terms from 1859 to 1863. In 1869, during his second term in Congress, he married Kate Ross Brodhead and they had four daughters.

During his first term in Congress, Van Wyck delivered a harsh and widely reported antislavery speech on the House floor in which he denounced the Southern states for slavery. A year after his anti-slavery speech in Congress, and on the same night as an attempt was made to assassinate president-elect Lincoln in Baltimore, Maryland, Van Wyck was attacked near the U.S. Capitol building by three men in an assassination attempt, reportedly in response to the speech. Van Wyck fought off the attack, surviving only because a copy of congressional records that he kept in the breast pocket of his coat had blocked the blade of a Bowie knife from going into his heart. The three men fled and were never identified.

After his second term in Congress, Van Wyck entered the Union army as colonel of the Fifty-sixth Regiment, New York. He was the idol of his men. His purse was always open to his soldiers, and he would write letters home for those in his regiment who could not write themselves, as well as pay for the postage. Van Wyck went on to serve in the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign and was wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks in Virginia. He left the army as a brevetted brigadier general. After the war, Van Wyck returned to Congress and served two more terms until 1871.

Van Wyck then moved to Nebraska and took up farming, but he did not stay away from politics for very long. After serving as a delegate to the Nebraska constitutional convention in 1875, he was elected to the state senate.

In 1881, Van Wyck returned to Washington as a Republican senator from Nebraska. In the Senate, Van Wyck specialized in attacks on local businesses and corporations and the wrongs suffered by the population at the hands of public franchises. He fought hard against street railways and gas companies, attempting to cap gas prices. After an unsuccessful run as a Populist candidate for governor of Nebraska in 1892, Van Wyck retired from politics and returned to Washington to live out his years.

The Holy Cross Episcopal Church that once sat on a triangular lot on Dupont Circle directly across from Van Wyck’s house had been in financial trouble for a long time. The wealthy around Dupont Circle tended to be Presbyterian, and the Church of the Covenant was just one block south of the circle. No longer able to stay afloat, the parish put the church up for auction; Van Wyck bought it and presented it to his wife, Kate, as a “little after-dinner favor.”

One day, Van Wyck astonished the fashionable Dupont Circle neighborhood by suddenly moving his family into the deserted church while repairs were being done on his Massachusetts Avenue house. Due to increasing illness, Van Wyck had developed a fear of climbing stairs and thought it would be better to live on a single floor. He initially divided the auditorium by imaginary lines into parlor, bedrooms, dining room and a picture gallery that later became real walls and rooms. Van Wyck would often be seen sitting on the lawn in front of the church in his shirt sleeves, smoking a cob pipe, and nodding to those passing by and staring.

Van Wyck died of a stroke in 1895, and a year later, his widow Kate sold the church and its lot on Dupont Circle to Herbert and Martha Wadsworth of New York City.

Fortunately, for the neighborhood’s Episcopalian population, Calvary Parish had formed and built its own parish hall on Church Street just three years before and would complete the construction of its new St. Thomas’ Parish on Eighteenth Street in 1899.