The Knickerbocker Theater: From Upscale Cinema to Psychedelic Dance Hall

Updated and Expanded: March 25, 2025

The collapse of the Knickerbocker Theater's roof in Washington, DC on the evening of January 28, 1922 brought tragedy not only to those inside, but also later to its owner and architect. Reborn as the Ambassador Theatre the following year, it would continue to survive until the 1960s.

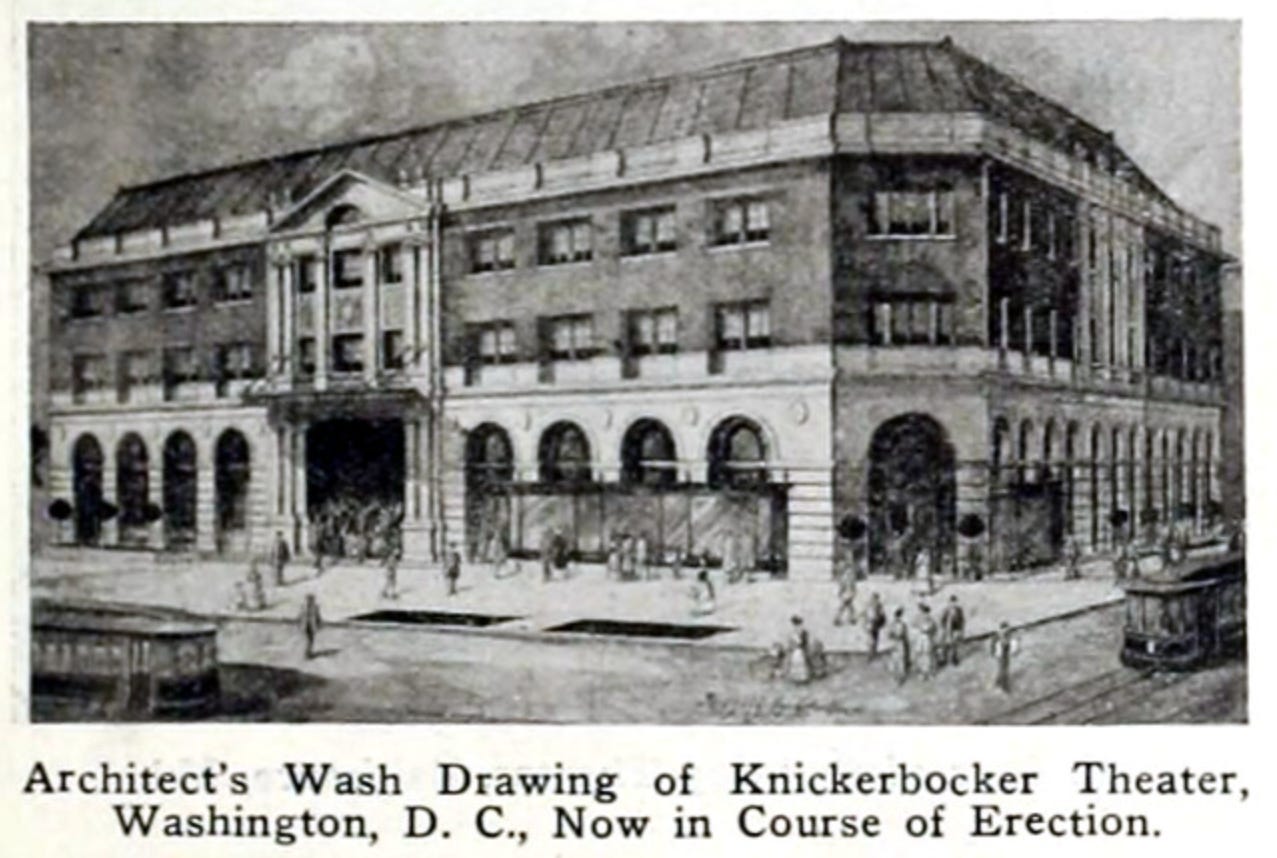

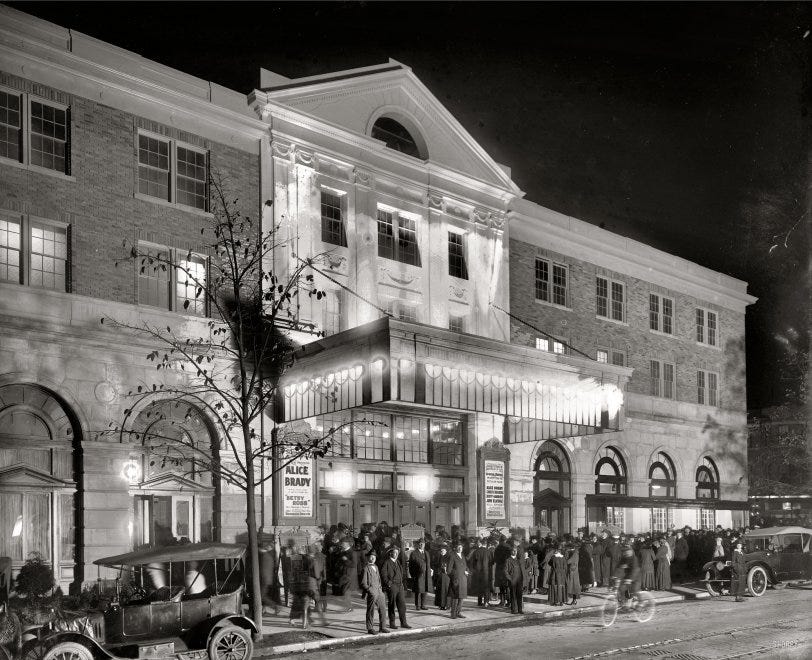

The Knickerbocker Theater once stood on the southeast corner of Eighteenth Street and Columbia Road NW. It was built in 1917 for the Knickerbocker Theater Company, owned by businessman Harry Crandall. At one point, Crandall owned a chain of 18 theaters in Washington D.C., Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia.

When it was completed, the Knickerbocker Theater was the largest theater of its kind in Washington. In addition to serving as a movie house, it was also used as a concert and lecture hall, with ballrooms, luxurious parlors, and lounges.

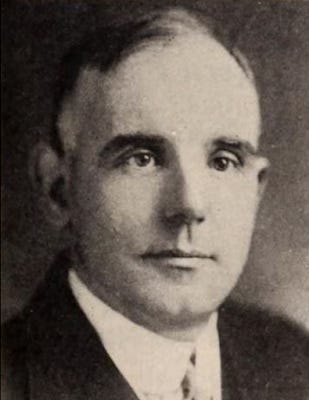

The Knickerbocker Theater was designed by architect Reginald Wyckliffe Geare. Due to the war, there was a shortage of the heavy-weight steel roof trusses and weaker ones were substituted for what was needed to support the theater’s flat roof. Also, structural brick was replaced with hollow brick for most of the exterior walls, not able to provide the necessary load bearing support for the heavy, flat roof. Geare ultimately approved these modifications to his original plans.

On January 27, 1922, Washington experienced its largest snowstorm on record. By the next morning, the total snowfall had reached eighteen inches, and when the storm tapered off the next morning, the official total was twenty-eight inches. Temperatures stayed in the low to mid-twenties during most of the storm.

On the evening of January 28, 1922, seeking a respite from the cold and snow, neighborhood residents flocked to the Knickerbocker to see the 1921 silent movie Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford. Due to the low temperatures during the storm, snow had rapidly been accumulating on the theater’s flat roof.

During the intermission of the movie, the weight of the snow split the roof down the middle, bringing down the balcony as well as a portion of an exterior wall, burying dozens of people.

By midnight, 200 rescue workers were on the scene, and that number increased to more than 600 by 2:30 a.m. Nearby residents, including the theater’s architect, Reginald Geare who lived just a few blocks away, helped pull bodies from the debris and fed the rescuer workers. Geare’s knowledge of the building’s design —and the shortcuts he took in its construction—proved invaluable in the rescue work.

In all, 98 people were killed and 133 injured. This disaster still ranks as one of the worst in Washington, D.C. history, and the storm is still known today as the Knickerbocker Storm.

In 1922, Reginald Geare, along with four other men, was indicted by a grand jury for manslaughter. Geare was charged with failing to draw the plans and designs of the theater in a skillful manner and failing to exercise proper supervision of work while the building was being constructed. None of the men were ultimately convicted.

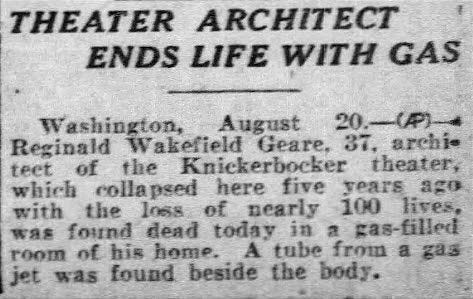

Geare’s career as an architect was destroyed by the disaster. Although he fought to reestablish his career, he would never be able to recover from the blow and committed suicide in 1927 by turning on the gas in an attic room at his home in the Cleveland Park neighborhood of the city.

Crandall was not deterred by the Knickerbocker disaster. In 1923—only a year later—he hired architect Thomas Lamb to build a new theater in the shell of the ruined Knickerbocker Theater, now to be called the Ambassador Theatre. Lamb retained Geare’s original Knickerbocker façade, but the rest of the theater was new. The 1,800-seat theater opened on September 20, 1923 with the Warner Bros. film “Main Street.”

With his theater empire going bankrupt, Harry Crandall committed suicide in 1937 after he lost his final comeback project in Cleveland Park that had opened as Warner Brothers’ Uptown Theater the year before.

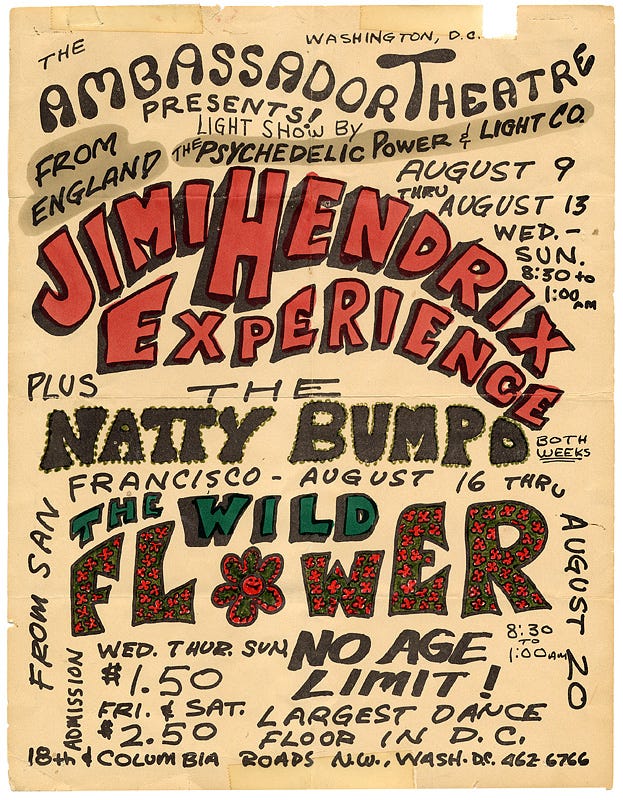

By the 1950’s, the Ambassador Theatre was struggling and there were multiple attempts to keep the theater in use, including as a psychedelic dance hall in the 1960s. The balcony was used to house multiple projectors and black lights to splash the walls with colors and images. This became a stand alone show of its own with tickets priced at $1.50 on week nights, $2.50 on weekends.

The mezzanine level of the dance hall hosted a head shop selling lava lamps, posters, as well as other hippie paraphernalia. The concert hall also sometimes functioned as a community center reaching out to neighborhood kids for special matinees and served as a staging area for the anti war march on the Pentagon.

In August 1967, Jimi Hendrix and his band The Jimi Hendrix Experience performed at the Ambassador for five consecutive nights. Tickets for the show started at $1.50.

The psychedelic dance hall lasted for only about six months. The Ambassador finally shut down in 1968 and the following year it faced the wrecking ball—not to the dismay of many in the neighborhood.

Perpetual Savings & Loan Association constructed a bank on the site with a public plaza in 1978. It eventually became SunTrust Bank, and then Truist Bank before Truist moved its services across the street.

In 2016, Hoffman & Associates proposed building a six-story residential building on the site. The proposed development was controversial and led to community pushback and court proceedings. Ultimately, Truist donated the property with the now-shuttered bank branch and plaza to the nonprofit organization Jubilee Housing.

Jubilee has unveiled plans for an all-affordable housing development with a seven-story and penthouse development with approximately 50 residential units. The project includes retail spaces on the first level, and a community room in the penthouse. The plaza area in front of the building would remain a space for community events.